By Jennifer Daly

Synthesis of an Idea:

During this summer’s National Endowment for the Humanities two-week seminar “Transcendentalism and Reform in the Age of Emerson, Thoreau, and Fuller” we would get together for discussion forums on everything from our own writing to pedagogical practices to activism inside and outside the classroom. One evening, a professor had mentioned the Digital Thoreau Project as a way to show the students the synthesis of Walden and to track the very deliberate changes Henry David Thoreau made in each of the manuscripts. After much thinking, I had the thought that this could be done with almost any writer—as long as there was a manuscript. I decided that I would utilize manuscripts to open a conversation about process and revision with First Year Writing students this year and see if it was accessible to them. There was a chance that they a) wouldn’t care, or b) it would fly over their head never to be seen or heard again. I was hoping for many things—none of which involved calling the lesson plans a total loss.

A huge part of the revision process is being able to disagree with yourself, and I think this is something the students grapple with the most. I know I did when I was a student, and I still do today. Just recently I was reviewing an essay I had written a few years back to prepare applications for PhD programs, and as I reread the essay and worked on some revisions, I realized that I did not agree with myself at all. Cue existential crisis—do I even know myself?! This is a story I have told all of my classes this semester. It is important for them to know that it is ok if they reflect on their work and find that they don’t agree with it. That means they are growing and learning: the two most important results of their educational career. I had difficulty with this, and I tell them about how I reached out to my own mentors in a state of panic (thank you, Caroline Dadas and Tatum Petrich!). I like to think they find it amusing while also absorbing the notion that it’s ok if they don’t agree with their former selves.

One of the goals that I feel is incredibly important about this lesson plan is to show the students that even the most respected writers—the writers that we cherish and look up to as a source of inspiration—revised their work. This not only shows them that the great writers they are so eagerly studying had to try again (revise and resubmit—I think we’ve all heard this one) but that these writer’s genius wasn’t just something that magically happened. Writing is work, writing is needy, and writing is never finished. It seems as if revision is one of the tougher ideas to convey to students. I have found that the reason for this is anywhere from their claim that they just hate to look back at their own writing, to the energy it takes to consider revision, to not understanding how to do it, and every reason in between those. As a professor who is just starting out, I am sure I will hear many more reasons as time goes on … But revision is an incredibly important part of the writing process, and without it writing is only subpar. The task, then, is to convey this important aspect of writing in a way that the students both understand and appreciate.

While in Concord, the group was lucky enough to gain access to the archives of the Concord Free Public Library, and deep down in the basement we were shown a manuscript from an address Ralph Waldo Emerson gave in Concord, Massachusetts. This was an original document beautifully sealed so one could most certainly touch it without hurting it, and the truly marvelous parts of it was the marginalia that sprawled every page. There were scratch outs and rewrites that circled the margins—some started at the top and worked their way down, others were in the form of footnotes of new information Emerson found in his readings—here existed a living, breathing thought. It was magical to see the transformation happen. The notes that were most interesting were the ones that disagreed with the speech itself. I hope that when the students see synthesis like this they realize that it doesn’t make them a bad writer to discard older thoughts and write new ones, that it gives them the courage to take chances and be wrong, that sometimes the safest route isn’t always the best route, and that revision is a natural part of the writing process for all writers—even experienced ones.

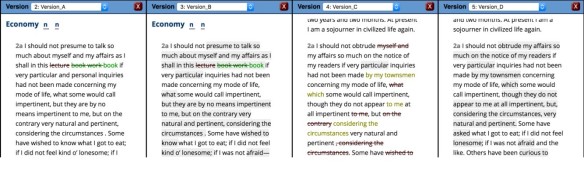

This is an activity that can be done with any writer that has available manuscripts. Some images of manuscripts can be found online, and you most certainly don’t need entire works. Utilizing a writer the class will read and discuss in class is helpful because the students will already have an idea of the end product. When it comes time to look at the manuscript, they already have a firm base of knowledge about the published version of the text, and magic happens when you start to compare them. To exemplify, below is an image from DigitalThoreau.org:

Image used from the introduction on digitalthoreau.org, Paul Schacht

The beauty of this particular example is the very evident way that Thoreau removed and added words, changed language, deleted text and added, and the way that the images are placed side by side allow the viewer to watch the transformation happen. DigitalThoreau.org makes it easy to have a discussion about the journey of Walden from idea to publishing. Now, for the fun stuff. Below you will find my lesson plan goals, discussion driving questions, and the student response to a class I taught on “The Declaration” and “The Constitution.”

What Happened in the Classroom?

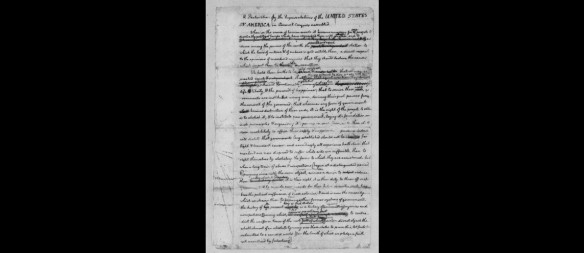

The assignment for the class that day was to read “The Declaration” and “The Constitution,” which meant the students should have an idea of what the discussion was going to be about. After some discussion on the physical texts, I brought in the images of the manuscript found here from the Library of Congress:

https://www.loc.gov/resource/mtj1.001_0545_0548/?sp=1&q=Declaration+of+Independence

https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/tr00.html

“The Declaration of Independence” image from The Library of Congress

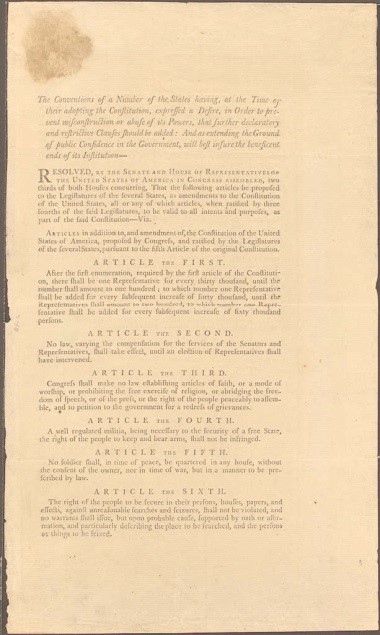

“Madison’s Copy of the Proposed Bill of Rights” image from The Library of Congress

I pulled up the images on the computer to project them to the class and we took a few moments to adjust to the handwriting (it is fabulous that digitalthoreau.org digitized the drafts because handwriting can be difficult to work with).

Next, we tried to decipher what was scratched-out. We utilized the completed versions we read, and tried to figure out what was under those scratch outs and posit why Jefferson and the forefathers decided when change was needed. We searched other copies of the documents to see if there were clearer images out there to help us discern what was hidden under the slashes and lines. We watched this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bFXGztm89nI which provides some nice historical information and had a fruitful discussion about the impact that multiple writers had on the document and the importance of teamwork in the construction of “The Declaration.” We then discussed the impact of the new words versus the old words and why such changes were made. I asked them to read the original and consider what that version meant: did it change or stay the same? It opened a conversation about how different America would be if some of these changes would not have been implemented, such as removing God from the original drafts, and the addition of the term “self-evident.” We concluded by speaking about how important the act of revision was in this American artifact.

I then did the same with “The Bill of Rights,” which opened up a conversation about what it means to change the original and disagreement with one’s self when we talked about the addition of the 13th and 19th amendments. The students were in awe with the images of the manuscript, and while some of them didn’t enjoy the activities because of the difficulty in deciphering the handwriting, overall it was a lively, fruitful conversation about the importance of making sure the writing you put forth is the best you can do.

Many library archives have digitized an abundance of their rare papers and manuscripts. You can locate almost any writer’s original papers and the libraries are great about providing digital copies of the pages for you. A simple search on Google will lead you to the library where the documents are held. Technology has made this possible and utilizing image with video and alphabetic text made this lesson plan successful.

Reblogged this on Ron Brooks.